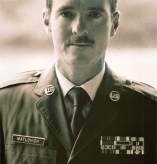

| July 2nd marked the 25th anniversary of funeral services for former TSgt. Leonard Matlovich, a 12-yr. veteran of the United States Air Force who had been awarded a Bronze Star for bravery, and a Purple Heart for wounds sustained when a landmine blew up in his face in Da Nang, South Vietnam. Just as they had in 1975 when his story of being the first service member to purposely out himself to fight the military’s ban 18 years before anyone heard of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” exploded on the front page of “The New York Times” and on the “CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite,” starting, as documented in the video at http://youtu.be/u1T1sVVgrS8, an unprecedented public discussion about gay rights, mainstream media around the world reported his premature death. |

|

| “Matlovich Vietnam War Hero, Gay Activist Dies” - “AIDS Kills Ousted Air Force Sergeant” - “Matlovich, Pioneer Gay Activist, Dies.” Some erroneously reported that he’d received a dishonorable discharge. The Langley Air Force Base Administrative Review Board had actually recommended he get a General discharge, but Wing Commander Col. Alton Thogersen recommended it be upgraded to Honorable, an act he apparently remained so proud of that his family devoted a paragraph to it in Thogersen’s own obituary in 2012, thirty-seven years later. | |

In the Christopher Street West Pride Parade in Los Angeles a few days after Leonard’s death, festive spectators grew silent as a riderless horse passed before them, preceded by a man carrying a red, white, and blue banner bearing the words, “Sgt. Leonard Matlovich Hero.” Two weeks later, newspapers reported on his unique funeral, too. “Gay War Hero Buried With Full Military Honors” – “Matlovich Eulogized as Hero – Service Reconciles Life as Military Man, Gay Rights Activist.” At the church service in Washington DC, eulogies were delivered by gay Cong. Gerry Studds, and ABC’s “Good Morning America” anchor Charlie Gibson who, after Leonard revealed on the program the year before that he had AIDS and called the Reagan Administration “criminal” for their indifference to the pandemic, told his co-host, “He’s a remarkable individual. There are people you meet as a reporter that you come to care about, and he’s one of them.” At Leonard’s request, music was provided by the DC Gay Men’s Chorus. Then his coffin was born through the streets of the nation’s capital on a horse-drawn caisson in an historic cortege led by mourners carrying both American and rainbow flags, and accompanied by an Air Force Honor Guard. His mentor, modern gay rights movement icon Frank Kameny who had conceived of the test case, wearing his WWII blue and silver Combat Infantryman's Badge on his lapel, and gay Army Sgt. Perry Watkins and lesbian Air National Guard Lt. Ellen Nesbit who were still fighting their own discharges walked beside the caisson all the way to historic Congressional Cemetery where each spoke about his unprecedented contribution to the fight for gay equality and dignity.

Kameny said, “The Air Force finally did it right and on Leonard’s terms today. It’ a pity they didn’t do it 13 years ago.” Watkins said, “The most formidable weapon against [the country’s] cold, uncaring, and misguided attitudes is the love, unity, commitment, and devotion Leonard exhibited so proudly. His example lets each individual know that they must take a personal stand, with pride and courage, so that the dream we all share will continue to move victoriously forward.” Nesbitt encouraged everyone to also continue his AIDS activism, and thanked his parents “for instilling in Leonard so much love, courage, and self-respect.” Three rifle volleys cracked the summer air, “Taps” sounded across the field where Walt Whitman’s great love Peter Doyle also rested, and his Mother was presented with the American flag that had covered the coffin of the first gay recipient of the Purple Heart the world had ever known. As everyone left the cemetery, none imagined how often his epitaph, “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one,” would echo again and again over the many years left to end the ban. Nor how his then-fresh gravesite would turn into an internationally recognized place of pilgrimage and celebration; the scene of Veterans Day observances, DADT protests, the starting and finishing point for DC Front Runners recent 5K Pride Run, a gay commitment ceremony, and the legal marriage of gay Army Iraq veteran Steve Hill and his partner Josh Snyder. Nor how many gay men and women, individually and as couples, would choose to take their own final rest near him, having remembered his words: “I believe that we must be the same activists in our deaths that we were in our lives.” The most recent, only some 15 yards away, was a 1947 graduate of West Point. A national LGBT veterans memorial is planned nearby, and Paul Williams, Congressional Cemetery President, has indicated 10 more individual plots have been purchased so far this year alone.

To the swarm of reporters outside his 1975 discharge hearing, Leonard said: “Maybe not in my lifetime, but we are going to win in the end,” unsuspecting how short his remaining lifetime would be. A quarter century later, while LGBs can finally serve openly, the fight for their full equality in the military goes on, one which he’d be leading were he still with us. Each spring as the blossoms from the cherry tree that now shelters his grave fall gently upon its black granite, I’m reminded of the words of W.B. Yeats:

|

“Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths, |

..............................

Michael Bedwell is a member of the board of Out Military, a past president of DC’s Gertrude Stein Democratic Club, and creator of the Website www.leonardmatlovich.com